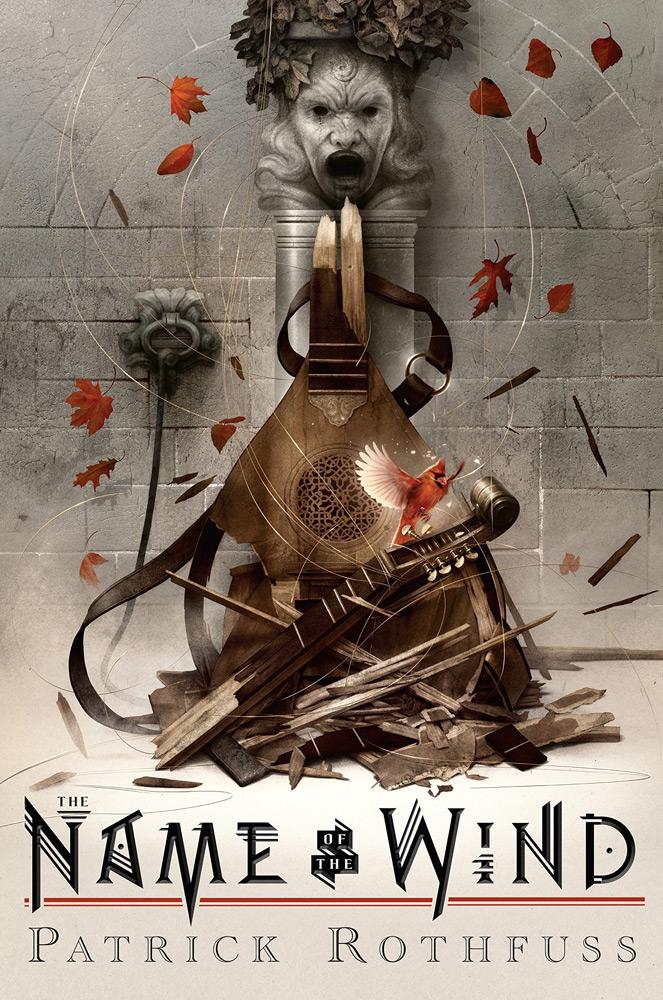

You may have heard of him

Patrick Rothfuss’ tale of tragedy, power and love

January 21, 2020

Book 10/10

In a land built upon myths, legends and mystical secrets, only one thing is sure to bend the world to the wielder’s will: Names. Not just any name – no, it must be a deeper name, one that slips off the mind as quickly as it does the tongue, for these are the names that can command the sea, the thunder and most relevant, the wind. Patrick Rothfuss’ “The Name of the Wind” focuses on a monolithic legend of a man named Kvothe; a broken man in hiding from a broken world, is sought upon by a chronicler to tell the honest tale of how he came to be one of the most notorious “heroes” of his age.

The story begins at the Waystone Inn, located in a tiny backwater town in the middle of nowhere, which sees hardly any visitors and hears nary a note of music; though the beds are warm and the food is good. Keeping the inn is a man who calls himself Kote, a man with hair as red as flame and scars both physical and unfleshly. One day a man named Chronicler arrives at the Waystone in search of a legend named Kvothe, though not in the way he was expecting. While on the road, his life was saved – through no small feat – by the very same man who wipes the bar before him. With what Chronicler has seen and what the fire-headed man saved him from, there’s little denying he’s found who he’s looking for. However, the pain of remembering Kvothe’s life would be less like ripping off a bandage and more like a surgical procedure; slow, methodical, precise. Ergo, Kote begrudgingly agrees to tell his story, but only on the condition that he have three days to tell it; this book chronicles the first.

Kvothe’s life begins more or less perfectly, being born into a well acclaimed family of performers; the Edema Ruh, his people are called, known for their crimson locks and semi-nomadic lifestyles and unparalleled performances. They travel in troupes of actors, singers, musicians, jugglers, storytellers and more. Kvothe’s father is the unofficial leader of this troupe, with his mother a close second. From his populous family of performers, Kvothe learns of all things entertainment; from plays and their parts, music and their meanings, lutes and their strings, to beyond.

One day the troupe happens upon, and adopts into their ensemble, a traveling Arcarnist  named Abenthy. Arcanists are those who’ve been educated and trained in nearly every respect at the University, from chemistry, history, alchemy, to forms of magic, like the Alar, Sympathy and Names. Abenthy’s kind are rarely welcomed outside the walls of larger, un-superstitious towns and cities, often believed to be dealing with demons and whatnot. During his time in the troupe, Abenthy truly became a part of the family; he concocted new face paints and makeups, colored lanterns and more. Perhaps most importantly, he spent the vast remainder of his time teaching Kvothe all that he could teach to an 11-year-old boy. As with everything else, the boy caught on remarkably quick, learning more in the following months what Abenthy learned in the span of several years.

named Abenthy. Arcanists are those who’ve been educated and trained in nearly every respect at the University, from chemistry, history, alchemy, to forms of magic, like the Alar, Sympathy and Names. Abenthy’s kind are rarely welcomed outside the walls of larger, un-superstitious towns and cities, often believed to be dealing with demons and whatnot. During his time in the troupe, Abenthy truly became a part of the family; he concocted new face paints and makeups, colored lanterns and more. Perhaps most importantly, he spent the vast remainder of his time teaching Kvothe all that he could teach to an 11-year-old boy. As with everything else, the boy caught on remarkably quick, learning more in the following months what Abenthy learned in the span of several years.

But then came the day Kvothe returned from gathering wood to a desecrated camp. Blood and blue flame littered the wreckage; a sight burned into his memory, right beside the grinning face of an ashen, black-eyed man, one of the seven figures who took his family from him.

Where could he possibly go now? Even with its labyrinthian spider’s web of a plot (expertly crafted, mind you), Rothfuss’ enchanting, patient prose bestows to the reader a flavor of rapture only managed by the beauty of a true work of art.

Images courtesy of Amazon.com & Wikipedia.org